This is an extract from the OPIP book. Previously, (B)obby and (A)lice discussed how psychology plays an important role in physics. As part of that discussion, Bobby made the case that physicists should maintain a sober stance toward their own achievements and shouldn’t get too excited too quickly.

A: While that’s all true, in practice physicists get judged, respected, and rewarded according to their work…

B: That’s right, the environment also has a fair share of responsibility for creating individuals’ egos. The psychology of “the rest of us” is as important in fostering or hindering progress in physics as that of the involved physicists.

A: In which way?

B: You just hinted at it—if we, the masses, think, “Oh, this person came up with that great theory; let’s give them money and recognition and ignore all the rest,” then it’s not surprising that it leads to individualistic behavior.

A: What do you propose? Less recognition for those who bring us progress?

B: We should give recognition when it’s due, but not idolize them like demigods. Let’s take the edge off of that, just a little bit. The way I just proposed physicists should see their achievements should also be how the public views them. For the same reason, anything that even remotely resembles a cult is wrong and dangerous.

A: And great achievements are never truly the achievements of only one individual.

B: Yes, there are many others, mostly invisible, contemporaries that make it possible. The “Winner-takes-it-all” mentality isn’t only unfair, but it also sets the wrong incentives. We should appreciate everyone involved in the field, even if they appear less significant. In one way or another, they all push us forward.

A: The media likes to have heroes though.

B: Yes, the media plays a role too. They cater to our hierarchical thinking that developed through evolution, but is now outdated and flawed.

A: How so?

B: Adoring the leader and striving to mate with the strongest of the tribe was often beneficial in evolution. First, it improved our offspring’s survival chances because they would have those “strong genes” too. Second, the strongest of the tribe could provide the best protection for us and our offspring. Today, those benefits are mostly gone. Hooking up with the guy next door doesn’t reduce your children’s chances for survival anymore. It may even be preferable (from an evolutionary perspective) to date the low IQ, but high sex drive, testosterone-filled body builder, conceiving many children, compared to hanging out with the introverted, sexually inhibited Nobel laureate. Exceptions like Feynman, Einstein, and Schrödinger (all had many affairs, and at least two official children) prove the rule.

A: I get your point, but it’s not that easy. It may be that the original reason for our hierarchical thinking is outdated. However, it’s not outdated in the sense that it doesn’t play a role anymore. It’s still alive and well.

B: You mean because we believe in it, it makes it real?

A: Yes. Hence, we need to take that into account too. For example, it is often criticized that the Nobel prize can only be given to a maximum of three people[1], as that doesn’t account for the many cases where more than three people contributed to it. However, the issue is that if “everyone” gets it, it loses much of its attraction. We need to keep it selective, as the motivation to become a member of a distinguished club is gone if it’s not exclusive anymore.

B: So, you’re saying: in some cases it might be unfair to give the prize only to a few people, but it’s required to maintain its allure?

A: If you phrase it like this, it makes me look very mean.[2]

B: No, no, you may have a good point. It’s important to get all considerations on the table. Only then can it be analyzed holistically and we can come up with good solutions. In any case, we’re getting a bit off topic now.

A: Right. Let’s get back to your original thought: we shouldn’t overly glorify people, but have a sober look at their achievements.

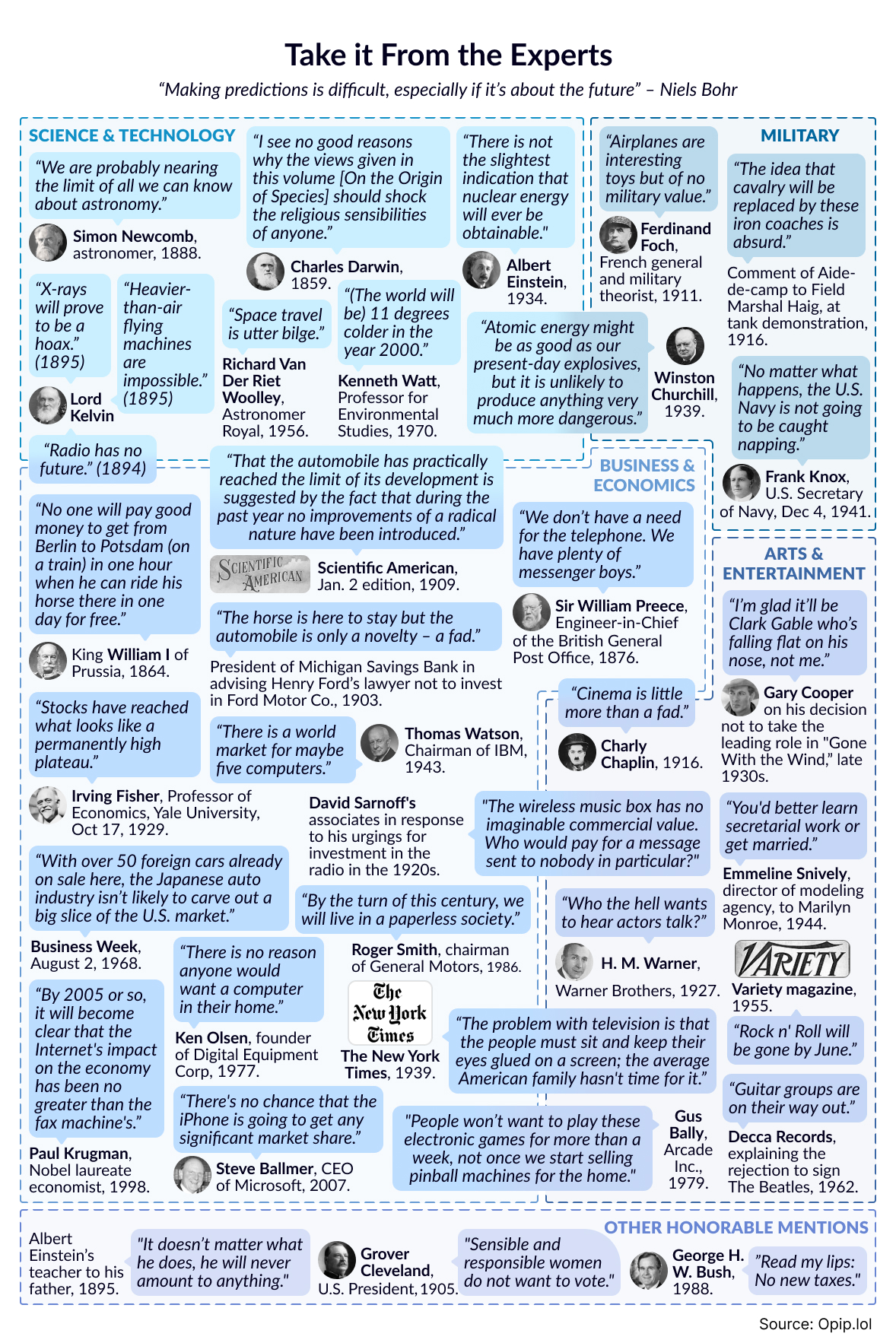

B: Yes, and for that, also the public should separate the ideas from the individuals. If we don’t, we run two risks, in different directions. For one, we don’t pay attention to good theories, only because they come from people we don’t consider high in our hierarchy, or whom we dislike personally. Second, we overvalue ideas from those who we consider high in our hierarchy (or those we like). Those effects even swap over to areas outside of physics. Some people give a lot of weight to statements from Nobel prize winners, even when these laureates are talking about subjects that aren’t related to their achievements in physics at all. It’s as if they got a “smart person talking, start listening, truth is coming”-stamp on their foreheads, no matter what they talk about. They often feel qualified to talk about topics outside their field of achievement as the success has gotten to their heads, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as “Nobel disease.”[3] It’s not justified, of course. Outside of physics, for example when it comes to the philosophical implications of physical theories, even accomplished physicists are just amateurs like you and me. Arguments are never valid just because they come from some form of perceived authority. Only because an otherwise accomplished person says it doesn’t make it right, and one plus one is still two, even if Hitler had said it. Every thought must be assessed on its own merits, regardless of who said it.[4]

A: And as you mentioned earlier, also experts can be wrong.

B: Right.

A: Any other ways how the psychology of “the rest of us” is relevant?

B: It’s relevant in determining which ideas get public attention. That plays a role in how resources are allocated. For example, some ideas in physics play with our imagination—postulating more dimensions, many parallel universes, the possibility of time travel—making them spread, simply because they are so fascinating. When you saw the time travel-thumbnail on that YouTube video the other day, you clicked on it, didn’t you?

A: Actually, I didn’t.

B: Well, some people did. And they did because it makes a good story. People love good stories. Personally, I find all of this a bit too fanciful. However, from a business perspective, it deserves respect for the successful promotional effect of it. Like in many other disciplines, when it’s about ensuring budget in physics, it comes down to good marketing.

A: Those cheeky little physicists, tricking us like that.

B: Oh, they’re no dummies. They know how to speak their funders’ language. Legend has it that William Gladstone, who became the British Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1852, once inquired about the practical value of Michael Faraday’s experiments, which seemed inconsequential but were funded by significant government money. In response, Faraday reportedly quipped, “I don’t know yet, but I’m certain you’ll eventually be able to tax it!”

A: Smart.

B: By the way, regarding “physicists tricking us,” I’m thinking in the opposite direction. Not the conjurer should be blamed, but rather we should take responsibility for allowing ourselves to get tricked. It reminds me of people accusing the news and TV industry of continuously producing low-quality content. Why does that happen? Well, it seems that’s what the public asks for. The news industry is a business that caters to what clients want. Ultimately, we’re responsible for it. If we want to stop that downward spiral, we need to call it out.

A: I get what you’re saying. Pointing fingers and criticizing physicists is easy, but not entirely accurate. The common person also has a responsibility for creating an environment that is conducive to physics to develop in the right direction.

B: Correct.

The book continues by discussing how ideas start out in physics… and end. getting your own, personal copy

—

[1] Hunt, K. (2023): “The problem with Nobel’s ‘rule of three’” (CNN).

[2] This reminds me of Louis CK’s “Of course, but maybe” routine, see Opip.lol/maybe.

[3] See Hartsffield, T. (2023): “Nobel disease: Why some of the world’s greatest scientists eventually go crazy” (Big Think).

[4] In the same vein, Picasso’s misogynism and Caravaggio’s notorious aggressiveness don’t make their paintings less revolutionary. Wagner’s anti-semitism and Lennon’s domestic violence don’t diminish the trailblazing nature of their music. Columbus’ brutal treatment of indigenous peoples and Newton’s zealous pursuit of counterfeiters (leading to several executions, for example of William Chaloner) don’t lessen the importance of their discoveries. It can be psychologically difficult to separate the art from the artist, but if we want to assess their work (not the person) objectively, then that’s what we have to do. If you think otherwise, then better not explore the lives of creators, as you will always find something highly disagreeable.