This is an extract from the OPIP book. Previously, B(obby) mentioned to A(lice) on several occasions that psychology plays an important role in physics, which is discussed in more detail in this chapter.

A: You mentioned earlier that psychology plays a role in physics. In which way?

B: Physics is supposed to be an objective, non-emotional and rational field for the common good. Ironically, it’s run by characters who are nothing but subjective, emotional, frequently irrational, and who seek to maximize their personal gain. That’s how nature made us, we’re all separate agents, striving to maximize our happiness.

A: You mention happiness a lot. If you now point to IncreasingHappiness.org again, you’re running the risk of overpromoting it.

B: Alright, I won’t.

A: What are the implications arising from the individualistic nature of the professionals in the field?

B: First, there’s the ego. For sure, many people enter the field hoping they’ll be the new Einstein. Being regarded as one of the brightest scientists on the planet feeds the ego more than three Oscars, two Olympic gold medals and becoming president combined. Plus, it often comes with some sweet dough: the Nobel prize winners get the equivalent of 989’822 US Dollars and 79 cents (but who’s counting[1]).

A: You think you could be the next Einstein?

B: Haha, no. Even if Subjectivity Theory was right, it wouldn’t be much of an achievement. The particular thing about it is that if it’s true, I may have been the only one who had a chance to come up with it, so there’s no reason to feel smarter than anyone else. I’m also not sure if I wanted to be in the limelight. It’s not as joyful as it looks. On the other hand, there is the money… I could buy a lot of things, starting with a recumbent bike—you know, one of those that…

A: Snap out of your dreams. It’s not going to happen.

B: Well, Bob Dylan got the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. In light of this, anything seems possible.

A: I don’t think it’s smart to make fun of the Swedish Academy’s decisions. For that reason alone, you can kiss your Nobel Prize goodbye.

B: Never mind. Chances were slim anyway.

A: I couldn’t agree more. Anyway, let’s continue. The ego aspect of things—is that a bad thing? If people enter the field because of it, then that sounds like a big driver and motivator.

B: Yes, that’s a big point on the pro side. Unfortunately, the points on the con side don’t look much smaller. To defend their “babies,” or brainchildren, physicists often make their theories intentionally fuzzy to escape refutation. This is often done covertly, in ways that are not easy to spot. Only a few physicists are as open as the cosmologist Lawrence Krauss, who said that he’s only making predictions for events at least two trillion years into the future, to ensure nobody will be around to check if he was right. The act of making theories irrefutable in plausible and non-obvious ways can even turn into an art. It’s bad art, but it’s still art. I say “bad” because it goes against the scientific spirit. But who cares about the scientific spirit if your ego, and sometimes career and paycheck, are at stake.

A: Yes, I can see why physicists become defensive about their theories. By the way, you’re not making things better with postulates like “There are no particles.” That won’t make you very popular among particle physicists. It’s even in their job titles. By doubting the existence of particles, you question their legitimacy too.

B: Sorry.[2]

A: What are the signs that physicists make their theories difficult to refute?

B: If someone proposes a model, and the average physicist cannot understand it, then it should be regarded very skeptically. It’s the task of the person who proposes the theory to make it comprehensible, not the task of the listener. Yes, physics can be complicated and “rocket science,”[3] but there is always the risk of misusing this fact and making theories more complex than they need to be. Apart from making theories more difficult to refute, there’s another incentive: it often feels good, as it conveys the impression that one is really smart, creating the idea of, “I was able to figure out something that complex.” In most cases, though, it’s more a flight of fancy than anything else.

A: Subjectivity Theory is not a flight of fancy?

B: Aha, there are different flights of fancy. Wild imaginations are okay—I was now talking about making things more complicated than they need to be. Subjectivity Theory isn’t complicated. You don’t even need to be a physicist to understand it.

A: And that’s a benefit of the theory?

B: Yes. Theories mustn’t be fuzzy, but clear and tangible. Subjectivity Theory is, in all probability, nonsense. But at least it’s tangible nonsense. I don’t mean this as a joke. As mentioned before, theories must stay clear so that they can be refuted.

A: Did ego also play a role when you conceived Subjectivity Theory?

B: I was hoping you wouldn’t ask. When it came to how to prove or refute it, I caught myself thinking, “Do I want it to be refuted easily?” That shocked me a little, as it raises the question of whether I’m living by what I’m preaching. As long as the outcome is correct (seeking refutation), it’s all good, but there is always this inclination… We’re all just humans.

A: Does the ego aspect have any other negative effects apart from trying to evade refutations?

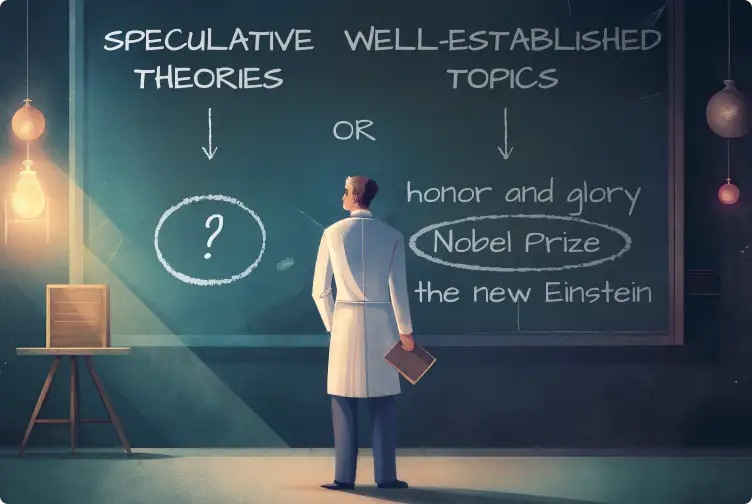

B: Yes, there are various examples. Professors pushing students to do research for their questionable theories is another example. Peer pressure is the same, just involving more people or an entire segment of physicists. It doesn’t always have to be overt, but can be quite subtle. For example, to advance in their careers, physicists need to publish papers and receive citations from other researchers (“publish or perish”). As a result, they may be more likely to work on popular, well-established topics that have a higher chance of being published and cited, rather than exploring more speculative niche areas. Even in supposedly sophisticated disciplines such as physics, you’ll still find a lot of tribal behavior.

A: That sounds very primal.

B: As primates, we’re still primal. This tribal behavior can also be observed in physics where specific theories are more supported in certain geographical locations rather than others. For example, while the Copenhagen Interpretation was named after its place of origin, it’s also a fitting name considering its strong support from physicists who worked and convened in Copenhagen.

A: …which led opponents of the interpretation suggest that “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.”

B: Naturally. Of course, believing in a certain theory should be based on its scientific merits, rather than the location you happen to be in (and the people by whom you’re influenced). This reminds me of an argument often used by atheists to illustrate the implausibility of believing in a particular God: if you had been born in India, you’d believe in Lord Krishna and Lord Shiva, if you had been born in Pakistan you’d believe in Allah, if you had been born in the US, you’d believe in Christ, if you had been born in classical Greece you’d be believing in Zeus. While these effects are much weaker in physics, they do exist. Hence, if you’re physically close to Copenhagen, ensure that this proximity doesn’t influence your belief in the Copenhagen Interpretation (and don’t make Niels Bohr your God[4]).

A: You’re digressing. We were talking about the negative effects of the ego on science. How could those be reduced?

B: For a start, let’s try to separate ideas from the individuals who came up with them. As long as physicists regard theories as their babies, chances for an objective assessment are slim. Love makes you blind. No matter how ugly the baby, every mother thinks it’s the most beautiful in the world.

A: That’s understandable.

B: I noticed this often when playing chess. Sometimes I come up with moves that I consider to be especially smart. More often than not, those are exactly the moves that turn out to be especially dumb. I fell in love with them, and that made me blind. Whenever a solution seems too perfect, with no apparent drawbacks, the reason is probably not that there are no drawbacks, but that something blinded us and we overlook them.

A: Is it realistic to expect physicists to judge their creations objectively?

B: The majority will probably always struggle with this. However, there have been several physicists who demonstrated an unbiased, sober, and critical attitude toward their theories. Einstein was very skeptical regarding the existence of gravitational waves and black holes, which are both predicted by his theory of relativity. Paul Dirac didn’t believe in antiparticles, which his theory predicted, until they were proven experimentally. Such views show a healthy stance with respect to one’s own creations.

A: But physicists still need to believe that some parts of it are true.

B: Of course. You could say they need to have an ambivalent relationship toward their theories. They should have sufficient belief to keep working on them but be skeptical enough to be able to make significant changes, as that will often be required to make them work.

A: I can sense that having such ambivalence isn’t always easy.

B: Indeed. As mentioned before, most people don’t like ambivalence or ambiguity. We want clarity. We want to know if something is good or bad. Keeping things in a “superposition” goes against our nature. Not giving in to deciding if you like or dislike (or love or hate) something can be challenging. Here again, the challenge is on a different level, it’s not calculating any formulas, but it’s a psychological one, requiring character. Improvement often starts at the edge of the comfort zone.

A: Regarding keeping ambiguity, I would be disappointed if you didn’t have a parallel in chess again.

B: And I don’t want to disappoint you. In chess, there are frequently complicated positions that could be simplified, for example by exchanging several pieces (less pieces on the board, less complexity). It’s tempting to simplify; we’re naturally drawn to it. Especially beginners love to simplify, even if it means entering an endgame where they are clearly worse. Many people prefer the worse but clear situation over the potentially good but unknown. Simplifying, releasing the tension, and getting rid of ambiguity can feel like a relief, but it also makes opportunities and solutions disappear.

A: Why is that?

B: The simple answer is that with more potential outcomes, the more opportunities there may be. However, there might be a deeper explanation. What does it mean to simplify? It’s making us understand the situation better. And what does “understanding” mean? It means mapping the situation to our existing frame of thought. Unfortunately, this framework might not allow the future solutions we need. I’ll elaborate more on this later.

A: Let’s get back to physicists falling in love with their theories. Any ideas how the risk for this could be reduced?

B: First, they should remember when they get an idea, it’s nothing more than a slightly different constellation of atoms in their brains. From an objective (or nature’s) perspective, it’s as mundane as you can get, and nothing special. Only we humans make it appear important, but it’s all made up.

A: That sounds a bit radical, but keep going.

B: Second, it’s important for physicists to understand why they are attracted to a certain theory. It could be the ringing of truth, but it may also be rooted in personal, deeply psychological reasons. Those wouldn’t be a good guide. For example, if your last name is Carroll, maybe you feel attracted toward stories of other bearers of your name, and wish to emulate them by placing you, Alice, into wonderlands and other parallel universes?[5]

A: I don’t get this one.

B: That was an insider now, you can ignore it.

A: That’s good, I already got into the swing of ignoring what you say.

B: Third, it’s important for physicists to remember that coming up with a great theory wasn’t their achievement, just a freak accident that it happened in their brains. Fourth, the idea has probably been thought of many times before (Goethe: “Everything clever has already been thought”). Fifth, it’s probably wrong, so stay humble (and don’t bet your ego on it). And finally, my sixth point is that you’ll be dead soon, so don’t get pumped up too much. All those realizations may put things more into the right perspective.

The book continues by discussing how the psychology of the public (the bystanders) also plays a role in fostering or hindering progress in physics. Get your copy now.

—

[1] The stated value of 989’822 US Dollars is for 2023 (converted from 11 million Swedish kronor, exchange rate as of November 2, 2023). In 2020-2022, it was 10 million kronor, and in 2018-2019, it was 9 million kronor.

[2] On a more serious note, questioning the existence of particles would force us focus our attention on exactly this area of physics, as we would need to explain something that goes against our current understanding. So, in fact, it would be good news for particle physicists. (Let’s hope this additional footnote will now stop the death threats from particle physicists.)

[3] Or “brain surgery,” see Opip.lol/mitchell-webb.

[4] While Niels Bohr’s writings might not fully capture it, he reportedly had a profound impact on people in person, attributed to his strong charisma. It’s said that physicists, after spending just an hour with Bohr, would often start to talk gibberish about the foundations of quantum mechanics, trying to follow and emulate Bohr’s thought process. Bohr was held in high esteem, a reverence that carried its own risks. John Archibald Wheeler once remarked, “You can talk about people like Buddha, Jesus, Moses, Confucius, but what convinced me that such people existed were my conversations with Bohr.”

[5] Sean, I know that my statement is nonsense. I just needed a theoretical example to illustrate the concept of physicists potentially being influenced by personal factors when gravitating toward certain theories. Thank you for serving as a hypothetical example here.